Five of My Very Favorite Openings in Fiction

How to kick-start a novel, how to hook a reader, and how to party-crash a genre.

Let’s talk about irresistible beginnings.

Some time ago, I was asked to do a presentation for an online mystery-writing symposium on a topic of my choosing. I chose to talk about masterful openings.

Speaking of which, this is not one — a masterful opening, I mean. (Sorry.)

This, however — from one of my favorite crime novels by one of my favorite crime writers — is:

Craft-wise, this is a classic flash-forward opening: We’re dropped in the middle of future action before being whisked back to the start of the tale. This opener plants in our minds an inevitable looming crisis, along with a bunch of intriguing questions: Our hero, Driver, will, at some point, wind up imperiled and regretful in a motel room (why?) with blood (whose blood?) pooling toward him and someone weeping (who’s weeping?) nearby.

Besides which, it’s beautifully written: the sly joke built around the double usage of “much later” / ”later still” (“Later still, of course, there would be no doubt”); the blood “lapping toward him” (with both its tidal and predatory resonances); the poetic insistence of the “pressure of dawn’s late light.”

If you can read this opening paragraph, then put that book down and walk away, you’re a more hard-hearted reader than I.

The necessity of a great opening, in any novel but especially a genre novel, should be obvious: it propels you forward, asserting an irresistible tug. But to me, a great opening is also a handshake, an introduction, a promise from the writer to the reader — a message that says: This is who I am. This is my sensibility. And this is the kind of ride you’re in for, should you sign up for the journey.

What I love most about Sallis’s opening is that, when you read it, you can’t help but think: I’m in the hands of a writer who knows exactly what he’s doing. Here’s someone in absolute control.

And that is a very thrilling invitation.

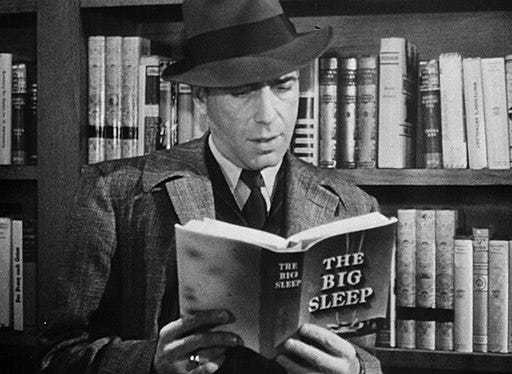

Here’s another famous hardboiled opening you might recognize:

I would argue that, for the first three sentences, this is simply a very good opening (and it should be, since it’s the opening of The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler), elevated by the glib snap of “the sun not shining” and that famous third sentence (“neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it”).

The fourth sentence? “I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be”? It’s perfectly fine.

But the fifth sentence — ”I was calling on four million dollars” — is the one that rings the bell.

It is absolutely impossible not to a) keep reading and b) settle back knowing you are in the assured hands of a masterful storyteller.

Here’s another legendarily great opening, just for fun, from Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle:

It starts, almost defiantly, with the simplest, most standard of introductions, like the “Hello” badge at a business conference or the beginning of a court confession (“My name is…”). Every sentence after that is better than the last; every sentence juices your interest and sharpens the story’s crystalline style; every sentence takes you somewhere new and disorienting and delightful (...with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf… I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise… Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom).

Then Jackson lands the knockout punch: Everyone else in my family is dead.

If there’s a more audacious and finely wrought opening paragraph in English literature, I don’t think I’ve encountered it.

The other thing I love about Jackson’s opening is that, like Chandler’s, it makes it very clear what’s ahead. If this voice, tone, and approach don’t appeal to you, great — because the rest of the novel likely won’t as well. But if it does — well, step right up.

When I was prepping for my presentation, I also revisited one of the most notable, if not the most notable, hardboiled openings: The one for The Maltese Falcon. True, this opening now reads as cliche — a knockout dame with a problem is ushered into a detective’s office — until you remember that Hammett invented the cliche and, essentially, the genre.

What’s most striking about this opening is the famous description of Sam Spade (“pleasantly like a blond Satan”). You don’t often encounter books anymore that contain prolonged physical descriptions of characters, let alone at the very beginning, let alone ones that break a person’s face down to a series of Vs. (Smarter writers than I can consider how physical description played a different role in fiction in what was essentially a pre-cinematic era — in this case, 1930.)

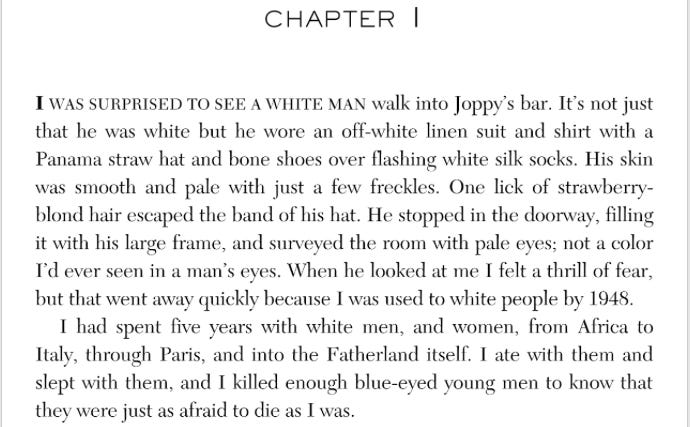

What I’d never noticed, however, until I prepared my presentation, is how Hammett’s opening is slyly echoed in another great crime novel’s opening: The Devil in a Blue Dress by Walter Mosley, published sixty years later in 1990.

Mosley is enough of a scholar of hardboiled fiction — and the opening to Maltese Falcon is famous enough — that there’s no way this echo is not intentional. (If Mosley’s ever addressed this directly, my quick search didn’t turn anything up, though unsurprisingly he does cite Falcon as a favorite novel.)

In Falcon, we meet the “blond Satan” with yellow-grey eyes and pale brown hair. In Devil, we’re introduced to a man whose “skin was smooth and pale” and who “surveyed the room with pale eyes.” (I have to imagine that Mosley is also partly winking at The Big Sleep, with its detailed description of Marlowe’s suit and socks.)

The difference, of course, is that in Falcon, Sam Spade is our protagonist, and the Ur-hardboiled detective — Spade is the trunk of the hardboiled family tree. In Devil in a Blue Dress, which is many ways is a revisionist take on the hardboiled genre, the central role, and the POV, belongs to Easy Rawlins, Mosley’s Black P.I.

Easy is the voice in our heads, the “I” in “I was surprised,” the one who’s describing this pale-eyed interloper, the one who’s “spent five years with white men… ate with them and slept with them,” the one who in the war “killed enough blue-eyed young men to know that they were just as afraid to die as I was.”

With this opening, Mosley is not only masterfully kickstarting his tale, with “just as afraid to die as I was,” that fantastic final sentence, as the great throaty roar of the engine catching. Mosley is also announcing to the reader and the world his arrival as an author to the genre — and signaling a sea change.

His character, Easy, is crashing the canon — a canon that up to that point had been dominated by stories focused squarely on, and told from the POV of, pale-eyed P.I.s like Sam Spade.

Mosley takes the most famous opening in all of hardboiled fiction, acknowledges it, flips it, then co-opts it. Easy sees these men, he knows these men, he’s stood shoulder-to-shoulder with these men, but he also stands apart — and now we, the reader, see him. This is Easy Rawlins announcing that he, too, belongs.

As openings go, it’s about as thrilling a beginning as I can imagine.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on these openings — and, even more, to hear about your own favorite openings, and why.

And now, for a closing:

Cheers,

Adam

For me, the all-time king of this is Charles Portis. Levi Stahl posted all of his page ones (there's only five novels, so easy) on twitter: https://twitter.com/levistahl/status/1229556525661859841

I can't help myself. The first one that came to mind was Don Winslow's infamous opening line to his short story "The San Diego Zoo" from his collection "Broken":

No one knows how the chimp got the revolver.