The Books that Belong on the Shelf with No Name

What happens when the novels you admire the most aren't like anything else at all?

I was taken with the question in this recent tweet:

It’s worth scanning the replies; I’m not at all surprised at the common responses — Dennis Lehane for crime, Agatha Christie for whodunnits, William Gibson and Margaret Atwood* for speculative fiction — as they are all inarguably masters.

But I’ve been thinking a lot about masterful books — the novels I’ve found, in terms of my own writing projects, to be most inspiring, innovative, and audacious. What I’ve realized is that most of those novels aren’t written by masters of a genre — because the books don’t slide easily onto a shelf like “Mystery” or “Science Fiction,” and their authors tend not to have a body of work that’s easily corralled.

Take Michael Chabon. To me, The Yiddish Policemen’s Union is the Platonic ideal of the kind of book I love to read and aspire to write. But is Chabon a master of that genre — and, if so, what’s the genre? Hardboiled alternative-history Yiddish fiction? Post-Golem speculative thriller?

All of Chabon’s novels are recognizably Chabon-esque, but it’s hard to argue that Union belongs to the same genre as, say, Wonder Boys. And that’s a big part of what makes the book special. It belongs on a shelf all its own, a shelf that defies classification — the Shelf with No Name.

Frankly, the books on this no-shelf don’t tend to be written by genre masters. Their authors are more like genre nomads, wandering brazenly across literary borders — or maybe genre mad scientists, cross-breeding genres to brilliant effect.

If you write books — especially genre books — you may occasionally need to revisit some of the novels that accomplish spectacularly what you’re striving (and sometimes struggling) to do. Those books may well be ones written by genre masters. But whenever I’m feeling creatively adrift, I poll my shelves for the no-shelf books — the ones that hit the bullseye that I’m trying to take aim at.

The trouble with seeking inspiration from these books, of course, is precisely that they’re one-of-a-kind — they don’t feel replicable. But they also inspire a certain essential kind of daring.

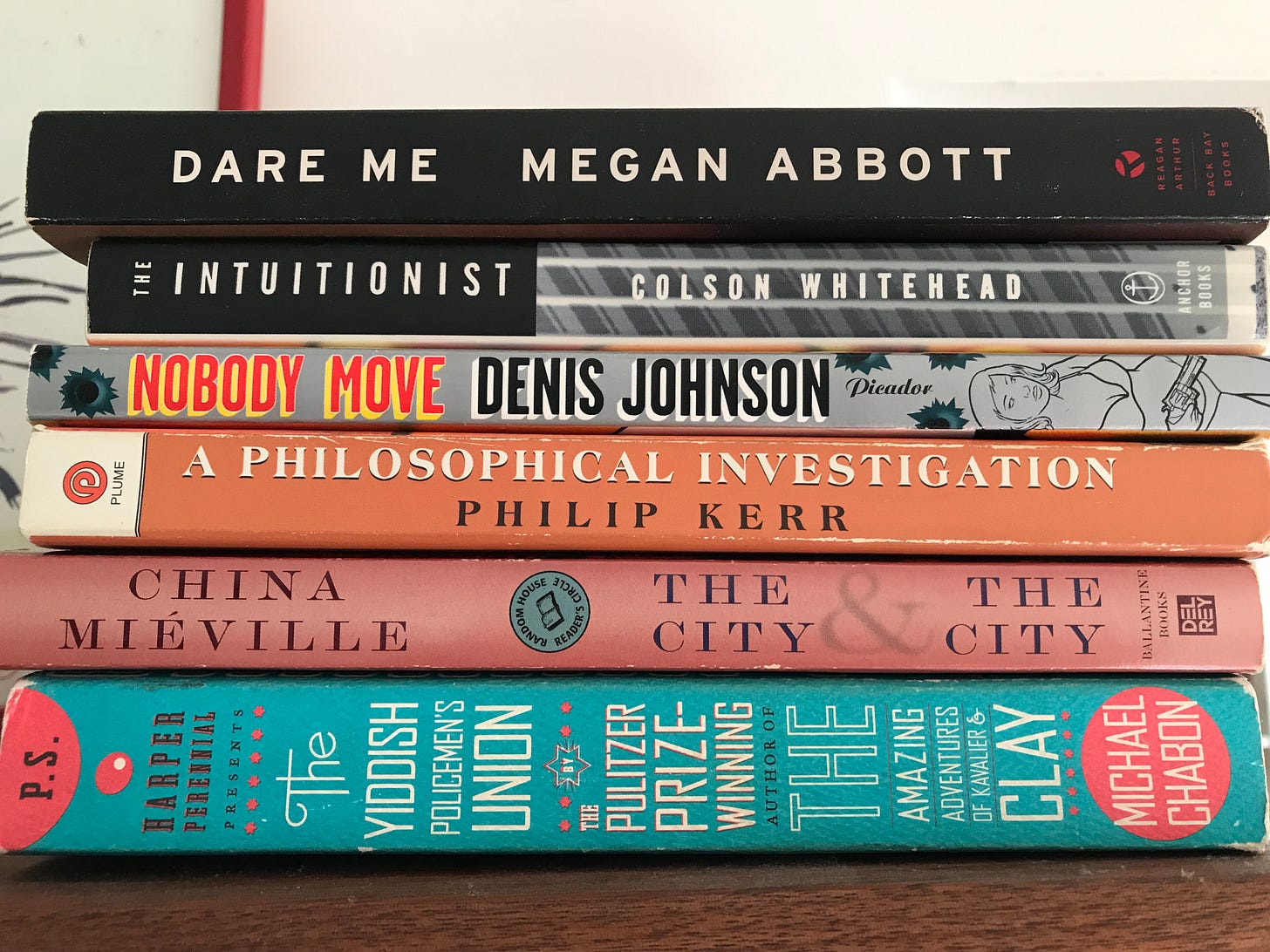

I keep a running list of these no-shelf books on my Notes app. Here are five I especially admire.

The City & The City by China Mieville

This is one of my favorite novels: a murder mystery set in the (fictional) city of Beszel, where two societies exist intertwined in a surreal state of mutual disregard and social impasse. Yet the ironic truth is that it’s the only book by China Mieville I’ve ever read. His other celebrated novels, like Perdito Street Station or Kraken, seem to belong to a realm of surrealist fantasy that isn’t precisely my literary kink. (Though, as noted, I should be more adventurous.)

This novel, though — reportedly written as a gift to his mother, a fan of police procedurals — is the perfect example of how a familiar genre form, with an intelligent twist, can yield a revelatory result. It’s maybe the smartest premise for a crime novel (or novel, full stop) that I’ve ever encountered, and the execution fulfills the promise of that premise masterfully.

Nobody Move by Denis Johnson

A favorite hobby of mine is reading Pulpy Books by Respectable Writers and this one might be the best. I’ve read other books by Johnson, which are reliably great, and which often show evidence of genre DNA. But in this one, about a schnook named Luntz who gets messed up with mobsters, then goes on the lam, Johnson rolls up his sleeves and goes Full Pulp, to glorious effect.

I’m thrilled when writers ignore or abolish the limitations that critics or fans try to impose on them. Movie directors do this all the time (Steven Soderbergh jumps to mind) and no one cares yet it feels somehow reckless when writers do it — especially critically established literary writers. But the result here is pure exhilaration.

A Philosophical Investigation by Philip Kerr

Kerr is better known for his excellent Bernie Gunther detective novels, set in and around WW2 era Nazi Germany. But I’ll always hold a special fondness for this 1992 standalone foray into speculative fiction, set in future London (okay, in the novel the year is 2013), with a plot about a female police detective racing to catch a cunning killer in a world where people are prescreened for sociopathy.

Part Silence of the Lambs, part Minority Report, this novel is thrilling evidence of what is possible when practiced writers create new worlds and write their own fascinating rules.

The Intuitionist by Colson Whitehead

Whatever happened to this guy? He dropped this brilliant debut and then… dropped several more brilliant novels, won two fiction Pulitzer Prizes, then launched a crime series (!!). I mean, the gall.

This debut, about a young elevator repair woman torn between warring elevator-repair factions, is a marvel: for starters, it dares to imagine, then effortlessly convince you of, a world in which elevator repair persons are culturally mythologized like private detectives. It’s genre fiction turned inside out, upside down, and sideways. A singular masterpiece.

Dare Me by Megan Abbott

Abbott’s entire body of work consistently serves up surprises – including her most recent novel, The Turnout, which was one of my favorite reads of 2022. I’m highlighting Dare Me here for how it ingeniously applies a noir template to the fraught, high-wire relationships of teenage girls, brilliantly evoking the life-or-death emotional tenor of high school life. But don’t trust me; trust this guy.

The problem with looking to any one of these no-shelf books for inspiration is that they’re all so singular as to be paralyzing. But I view them all, in awe, as proof of concept: of what is possible when these brazen genre experiments succeed gloriously. That assurance alone can be enough to prod you back into the lab to dust off your own test tubes.

Cheers,

Adam

* Gibson and Atwood — both Canadian! — are interesting examples: they’re genre masters, sure, but Gibson essentially invented his own genre (cyberpunk) and has been expanding its boundaries ever since. Atwood has written brilliant speculative fiction but is more like Chabon in that her body of work roams freely. She may have written masterful speculative fiction, but her mastery extends well beyond.

I read this post after writing some about finding your voice as a writer. Could your Shelf with No Name actually be a Favorite Voices shelf? How many of these authors would you follow into anything they write because of their singular way of writing?

Two of my favorite books are on your list, and I do agree -- it's the interstitial fiction that intrigues me the most. Not everything fits neatly in a box, thank goodness, or what gifts would we wrap in tissue paper, rubber bands and pillowcases?